Susan Leviton, one of only a handful of people today exploring and sharing the tradition of women’s a cappella singing in Yiddish, was not always a big supporter of all things Yiddish. In fact, she says, singing Yiddish was pretty much off her radar screen until she moved to Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, in 1984. What changed in Harrisburg was that she heard the Old World Folk Band, an instrumental group playing Klezmer (eastern European Jewish music), and soon became their vocalist.

Performing over the years with the Old World Folk Band and other instrumentalists and as a solo vocalist, Leviton says she has found that no matter how removed audience members may be from Jewish culture and Yiddish song, the material’s message and beauty bridge gaps when she does her job of thoroughly understanding and then communicating each word of a lyric and the emotional connections they create.

Learn here about Susan Leviton and her ability to communicate the richness of Yiddish music in her own words:

Q. How important was Yiddish in your household when you were a child?

A. My mother loved everything Yiddish. She always cried when she heard the songs, telling me over and over about how her mother, whom I never knew, sang those songs and told of leaving Russia at age 15, alone, and never seeing her family again. Those stories are so important to me now, but when I was a child, they really didn’t speak to me. My father had a great ear for music , but not a great range of interest. If he heard shlocky Jewish music playing on the radio on Sunday mornings (the only time it was aired), he would call from another room to turn it off. Interestingly, years later when I told my father that I had become a member of the Old World Folk Band, he positively lit up with joy and told me that his father, whom I’d never known, had played this music on the mandolin. While the combination of the two parental responses to the culture initially pretty much made me run the other way, the music ultimately has brought me many insights into my own life.

Q. You’ve had a long association with the Old World Folk Band. How did that come about and what has it meant to you?

A. About eight months after we’d arrived in Harrisburg, someone said I should check the band out. Until that time I’d never heard of them. The first time I heard them was at a gig they were playing in Washington, DC, at which I was exhibiting my artwork. (In addition to being one of the nation’s leading exponents of women’s a cappella Yiddish singing, Susan Leviton is a renowned visual and graphic artist.) I was very pregnant at the time and the band’s leader, Fred Richmond, invited me to come to a rehearsal after the baby was born. And so I did, hauling four-

week-old Noah to the rehearsal hall in a car seat. The rehearsal was overwhelming. The music was so familiar and fresh and I immediately sensed that it was running in my bloodstream. The power of that particular live music being created by people like me made me fall in love with the sound and the band at once. And it’s remained that way over these many years together. One of our favorite Old World Folk Band stories involves Fred handing me a stack of sheet music at that first rehearsal—without even hearing me sing—and saying, “We have a gig in Annapolis in two weeks. Why don’t you learn some stuff and we’ll see how you do.” Now, 25 years later, we still shake our heads at what he did and how I responded. I went home, got someone to bang out the melodies for me on a piano so I could learn them, and called my mother and told her she had to teach me to pronounce the words and what they meant. (That’s the payback for my parents using Yiddish as a “secret language” when I was growing up. Although I wasn’t engaged in the conversations, I’d heard Yiddish all the time because when my parents’ friends would come to the house and talk over coffee and cake, the conversations would start in English and, as time passed, first punchlines and then whole stories would shift to Yiddish. Coming to Yiddish through the music that I was learning reconnected me to a sense of warmth and friendship embodied in those words and songs.)

Q. How did you get from that initial exposure to Yiddish lyrics to the depth of knowledge and understanding that you have now?

A. My first exposure to the way to a mature embracing of the musical culture came in 1986 in a master class at KlezKamp, an annual gathering to promote a resurgence of Klezmer music and other Jewish folkart forms. In that class, Zalmen Mlotek, the instructor, who is now a dear friend, mentor, and colleague, urged me to “work on the Yiddish,” and that’s what I did. The process of “getting the words into my teeth,” of really learning the language I had heard growing up but never really assimilated, led me to discover a depth of material that I never imagined existed. Too many singers today think that if there are no Yiddish speakers in the audience and everyone is smiling and clapping, it doesn’t matter much that the language is being “faked.” But that doesn’t work for me. Native speakers remain my best teachers, and the ones who are the most helpful are those who cut me no slack. Today I read Yiddish when I can, slowly and with a dictionary, but most of my learning comes from analyzing song lyrics, studying phrasing, and in some cases literally painting a song before singing it so I have an opportunity to internalize a relationship with the lyric and the poet who wrote it.

Q. What comes first for you, the words or the music?

A. Because my primary concern is to communicate the meaning and story behind the words, I think that’s what generally engages me first. Then I fall in love with the music which, because it supports a language that has a different structure and sound than English, can’t be separated from the message. In much of Jewish music, the instrumental sound mimics the human voice, and that ability to communicate emotion through melody and traditional ornamentation is critical.

Q. How do you find the material you sing?

A. I snoop! I rummage through sheet music and books where knowledgeable booksellers can answer my questions. I needle musicians who play music that touches me and ask them to point me to vocal material in those styles. I have collections of books, some of which are all in Yiddish and await painstaking translation. But if I can pick out a title that is promising, or some indication that a song fits a topic that interests me, I get out the dictionary, sit down with native speakers, and get to work.

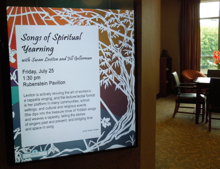

Q. You have a number of different themes that you have developed into concerts and lecture/demonstrations. What moves you into new and different areas to explore?

A. My interests at any given time can move me towards new material. Right now I am overflowing with interest in the early labor movement in the U.S. since 2011 marks the 100th anniversary of the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire in which 146 young lives were destroyed in 18 minutes. That tragedy led to mainly uppity working women leading the charge to establish our nation’s first worker safety laws. Today we are seeing workers’ rights and unions being eroded by anti-union legislation. One of my responses is to find more music! I recently translated a song that appears to be a Yiddish version of “Joe Hill,” a song about a young woman killed in gunfire at a workers’ rally. The lyric says that she never died and goes on inspiring us, even though her body lies beneath a draped red flag. I haven’t yet heard the music but I’ll get there! I find myself seeking out folk material and composed songs that allow me to build a repertoire of deeply meaningful and freshly relevant material. In the process, I have come to realize that my passion is to share the songs with larger and more diverse audiences. The songs are carriers of the culture, and like desert flora that burst into bloom with the rare rains, the songs come to life when they are set into context and sung with a full heart.

Q. One of the skills you’ve developed along the way is as a certified American Sign Language interpreter. Does that skill inform your singing?

A. From 1973, when I completed a master’s degree in deaf education, until 1984, when I moved to Harrisburg, my worklife was connected to the deaf community. I became a certified interpreter in 1975 and eventually honed my skills as a theatrical interpreter, working steadily on the stage interpreting plays including LaMama’s production of Shakespeare’s “The Tempest,” McCarter Theater’s “A Christmas Carol,” and “The Power and the Glory” at Philadelphia’s Annenberg Center. I was an interpreter for Swords Into Plowshares, a music collective that brought topical performers like Pete Seeger, Holly Near, Cris Williamson, Tom Paxton, and dozens of others to Philadelphia and I had the honor to share the stage. After settling in Harrisburg and finding my way back to Yiddish, I discovered that a familiar switch was thrown once I began to sing for audiences. Eventually I analyzed the process and realized that the narrative styles of American Sign Language (ASL) influence the way I use space and the consistency of my expressions and eye focus. ASL incorporates spatial references in the same way that our spoken language uses tense markers, pronouns, and plural forms to naturally tell a listener to whom and about what the speaker is referring. When I sing, I tell a story, so it is absolutely natural for my eyes to fall consistently in one area when referring multiple times to a particular character in a song, for my face to show a question, and for my shoulders to subtly indicate a relative distance into the past or future. Since I assume no Yiddish literacy in my audiences, the urge to communicate is served by a natural incorporation of the structures of Sign narrative style that visually reinforce my intended message. I

don’t think about it. I don’t “sign” when I sing, but I do provide a visual enhancement to the musical experience because my own language and cultural background is rich in ASL referents.

Q. There may not be too many people who are highly skilled in both music and visual arts and continue their careers on both tracks. How do you make this work for you?

A. Music and art are the conjoined twins of my life. I always painted and I always sang. My mother would hold her breath when she sent me to the store for a loaf of bread because I’d sing and dance my way across the street! There is now a wonderful symbiosis in my productive life. As a calligrapher, the ability to capture my understanding of a song as a visual expression goes right to the words. It’s joyful expression and often deepens my understanding of the material. Some of my most precious moments in art and song united have come when an older Yiddish speaker approaches a calligraphic painting and bursts into song—singing from my painting! Once, several members of a family that included Holocaust survivors and life-long labor activists stood clustered around a painting on display and sang the entire song together. It was a dream come true!