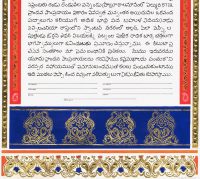

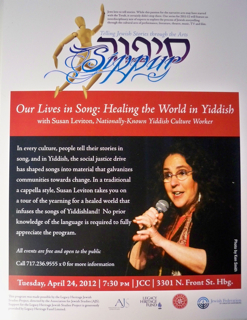

A self-described “Jewish Cultural Worker,” Susan Leviton has spent more than 20 years promoting and sharing Jewish culture through its visual and musical arts. In her Harrisburg Levworks studio she produces art works with paper and fiber, some translated into metal, Formica, and glass. Her ketubot (marriage contracts), awards, and institutional art are found in homes, synagogues, and awardees’ offices across the country and in Jewish communities as far away as Denmark and Ukraine.

Learn here about Susan Leviton and her ability to communicate the richness of Yiddish culture through fine arts.

Q. What role did art play in your life as you were growing up?

A. At age 2 I was “painting” with Q-tips and food coloring on paper plates. My mother never missed an opportunity to encourage me to play with color. A new box of Crayola crayons or a lump of clay were the best presents I could imagine. When I was growing up, our family spent part of the summer each year on Long Beach Island, New Jersey. This was long before it was a hip place, long before there was a highway directly to it, long before it was more that sparsely populated. I had the utter joy of spending whole days by the ocean, studying the changes in light on the water, noticing how colors differed from early morning to late afternoon, and examining sand grains, a few at a time, in their own subtle rainbow diversities. It was that experience, I think, that made me an artist.

Q. How about formal art training?

A. In the 1960s I attended Douglass College, a small, liberal arts women’s college at Rutgers University. I was an art major, but the reality is that the department was small and, except for a rather curmudgeonly art education professor, the entire faculty consisted of working artists in Soho who took the train to New Brunswick to teach. I received a rather unorthodox education, except for a brilliant “ by the book” figure drawing class. It seemed at the time, and in retrospect still seems to me to have been a most playful education. Only decades later did I realize that the very playfulness that causes me to qualify my “art degree” has given me a lasting and abiding freedom to look at problem-solving in art with great joyful freedom, never ruling out a color, material, or juxtaposition. Still, most of my work is pretty straightforward. It’s the process that remains for me the best of my 1960s’ hippie joy.

Q. I’m sure there are many things, but what’s one thing in your art that thrills you?

A. Holding spinning clay between the fingers of both hands as it rises into a form leaves me breathless no matter who’s at the potter’s wheel. One of the hardest things I’ve learned to do is to center clay on the wheel. It is very clear to me that what touches my aesthetic heart in pottery is the same thing in three dimensions that moves me in two dimensions in the lettering arts. What a truly beautiful pot offers is a created form that holds an elegant space within. And an elegant inked letter does the same thing. The counter (the space within a letter, like the shape inside a d or an a) is as important as the black ink around it. Pulling a pot and inking a line of text each craft elegance around an inner space.

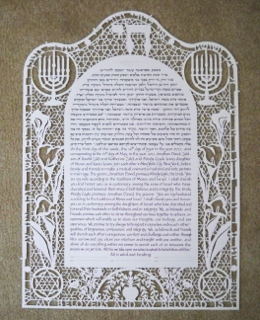

Q. Much of you work involves lettering ketubot and other items. Talk a bit about how you learned this art form and your approach to it.

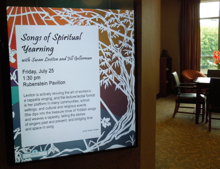

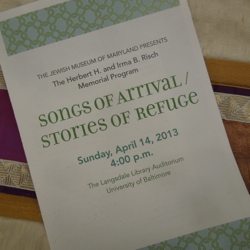

A. I took up lettering while I was teaching deaf children. For months I spent an hour or more every night at a tiny drawing table poring over a book on Roman lettering and filling sketchbooks with pages of single letters. I loved it right away! In 1981, curious about Hebrew calligraphy, I had the opportunity to study for a week with Ismar David, a renowned master of Hebrew lettering, who was in his mid-80’s. Ismar impressed on me that one must internalize the historic letter forms by analyzing manuscripts and high quality reproductions of classic lettering and then make a personal statement that is built on a solid foundation. Over the years I have had the opportunity to study with other master calligraphers, including Sheila Waters. As my interest in Yiddish poetry and song began to blossom, I found interpreting those words in calligraphic painting was a perfect accompaniment to the work I was already involved in—crafting traditional marriage contracts and a range of other ritual and decorative Jewish lettered arts.

Q. You also do a significant amount of work in papercutting and teach that art form in workshops. How did that begin?

A. The folk art of cutting paper or other thin materials is centuries old and universal. Jewish papercut art has two unique aspects that separate it from other traditional paper arts in Europe, Asia, Africa, and the Americas—virtually all Jewish papercuts serve a ritual function and they also make a direct reference to text. Thus, they rarely are “art for art’s sake.” My contribution to this rather old and quite ephemeral cultural expression includes working with traditional imagery and text references, but expanding the visual range to include contemporary settings, materials other than paper, and purposes for the papercuts that are themselves 21st century. For example, I have used images of Biblical flora to design eight-foot high papercuts for donor wall art in several institutions, and the material has been laser-cut vinyl, metal and Formica crafted to my full-scale designs. I believe the expansion of the craft contributes not only to Jewish arts, but to the expansion of the visual vocabulary for papercutting art worldwide. My work has been reproduced in First Cuts, the journal of the Guild of American Papercutters and as cover art for publications for the Women’s League for Conservative Judaism. One of my elaborate papercuts is featured in a traveling exhibit titled “Making it Better: Folk Arts in Pennsylvania.”

Q. There may not be too many people who are highly skilled in both music and visual arts and continue their careers on both tracks. How do you make this work for you?

A. Music and art are the conjoined twins of my life. I always painted and I always sang. My mother would hold her breath when she sent me to the store for a loaf of bread because I’d sing and dance my way across the street! There is now a wonderful symbiosis in my productive life. As a calligrapher, the ability to capture my understanding of a song as a visual expression goes right to the words. It’s joyful expression and often deepens my understanding of the material. Some of my most precious moments in art and song united have come when an older Yiddish speaker approaches a calligraphic painting and bursts into song—singing from my painting! Once, several members of a family that included Holocaust survivors and life-long labor activists stood clustered around a painting on display and sang the entire song together. It was a dream come true!